Civil rights hero has Waterloo roots

Posted

by Pat Kinney

on Wednesday, February 8, 2023

Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier Feb. 17, 2013

WATERLOO, Iowa --- Russell R. Lasley of Waterloo is a largely faded if not forgotten figure in the national labor and civil rights movements --- but not to those who knew him.

"He was one of my heroes," said Lyle Taylor, a longtime labor leader at The Rath Packing Co., where Lasley had worked.

"What a jewel," said Anna Mae Weems, longtime local civil rights activist who got her start through the union local at Rath.

Lasley died in Chicago in 1989. By that time, Rath had closed and his union had merged with another.

Today, one has to look closely to find Lasley's footprints in the sands of history. But they are there, and they are substantial.

An executive with the United Packinghouse Workers of America, Lasley, an African-American, brought the power of his union to bear to create one of the driving forces of the American civil rights movement --- the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

"I guess the Southern Christian Leadership Conference would not have existed without the Packinghouse Workers union," said King scholar Clayborne Carson, professor of history and director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University in California.

Lasley participated in the organizational meeting of the SCLC in January 1957 and served on its board of directors.

"I am sure the union provided the majority of the SCLC's budget when it first was established," said Carson, who was selected by Coretta Scott King in 1985 to edit and publish her late husband's papers.

Carson's research shows Lasley won the unwavering support of the SCLC and King when the union came under congressional investigation for alleged Communist activities.

Lasley and Rath

Despite his substantial role on the national labor and civil rights scenes, Lasley never forgot his Waterloo roots. He was a guiding force in contract negotiations and other labor matters at Rath.

At national conferences, "We'd always meet with him because he was from our local originally," Taylor said "He was a quiet, but very stern man, and when he spoke you knew it was fact," Taylor said. "He was also very reasonable, and when we came to meet with the company he'd figure out a way to resolve issues."

"He was a big, tall man, light complected, and had big hands," Weems recalled. "He'd slam his hand down on the table when making a point. We'd say, 'Don't break the table!" She also recalled he worked with the company to improve the flow of the meat-cutting operation on the shop floor.

According to Courier files, Lasley, born in Des Moines, grew up in Waterloo and graduated from East High School in 1932.

He went to work at Rath and became an official with UPWA Local P-46.

He was assistant chief steward during the bitter 1948 strike at Rath that erupted into a riot May 19 when a striker was shot and killed by a worker trying to cross the picket line. The Iowa National Guard was sent to restore order.

Lasley was one of several union officials criminally charged with conspiracy. He was ultimately fined $500 on a lesser contempt of court charge in 1951. Some union officials were sentenced to prison, but Democratic Iowa Gov. Herschel Loveless pardoned them in 1960.

In the meantime, Lasley, also a 1948 candidate for Iowa lieutenant governor on former Vice President Henry Wallace's Progressive Party ticket, was elected vice president with the UPWA international union that June in Chicago. Lasley moved there, resigning from the Progressive ticket.

It was at that point that the UPWA and Lasley became nationally involved in civil rights, according to records compiled by Carson at the MLK Institute at Stanford. The union began pursuing anti-discrimination activities in 1949 and formed an anti-discrimination department in 1950, which Lasley headed.

Lasley and the union crusaded against housing discrimination in Chicago, said labor historian Michael Honey of the University of Washington-Tacoma. "He was trying to open up housing for black families in white neighborhoods," Honey said. "When one home was surrounded and fire bombed, the union brought people out to try to defend the black homeowner. The Packinghouse Workers union was extraordinary. It probably was one of the few unions where whites would really come out and support black civil rights."

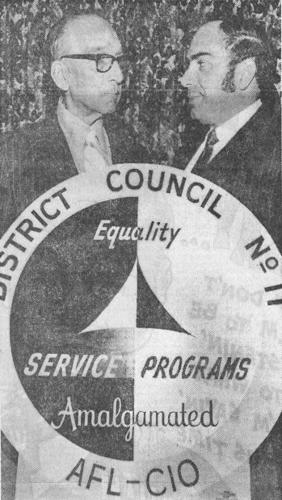

Russell R. Lasley, at left, is shown here with Waterloo labor leader Lyle Taylor at a regional conference in Waterloo in 1971. (Waterloo Courier file photo)

Lasley, union and King

The UPWA supported the Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott that began in late 1955. King led the boycott after Rosa Parks was arrested Dec. 1 for refusing to give up her seat to a white man on a city bus. "The enemies of Negroes are the enemies of organized labor," a UPWA resolution stated.

"The Packinghouse Workers union was one of the top financial backers of the Montgomery bus boycott. They poured a lot of money into that campaign," Honey said. "And they immediately had Dr. King come to speak at their conference in Chicago in 1957."

"When we're talking about that period of time, there weren't a lot of institutions that were firmly in support of the civil rights movement," Carson said. "Even within the union movement, the foundation of a lot of the unions were almost entirely white, and some had racial bars. The most supportive of all the unions at the beginning, probably the most crucial, were the (Brotherhood of) Sleeping Car Porters and the Packinghouse Workers union."

At the same time, Weems said, Lasley started a women's division within the UPWA and encouraged locals to do the same.

"He gave me my start" in local activism, Weems said.

According to Carson's MLK Institute research, in January 1957 Lasley attended the SCLC's organizational meeting. He called it "an extreme honor and privilege to represent UPWA in a conference of leaders who have dedicated their lives to the cause of freedom and establishment of a society free of racial injustice and second-class citizenship."

The union provided the bulk of the SCLC's first budget.

Carson said Lasley helped organize what became known as the "Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom," a May 17, 1957, march on Washington and rally at the Lincoln Memorial. It was there that King delivered his "Give Us The Ballot" speech, calling on President Dwight Eisenhower and Congress to ensure voting rights for African-Americans. "Lasley was among the key people in terms of organizing that initial march, long before the famous 1963 march" where King delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech, Carson said.

Lasley and HUAC

In 1959-60 the House Un-American Activities Committee investigated the UPWA for alleged communist activities --- and the union found support from King and the SCLC. According to online records at the MLK Institute, on June 11, 1959, King wrote Lasley a letter, stating "We are with you absolutely." He enclosed a statement of support for Lasley's union, approved unanimously by the SCLC.

The SCLC statement said the union and its officers, including Lasley, "have worked indefatigably to implement the ideals and principles of our democracy. ... It is a dark day indeed when men cannot work to implement the ideal of brotherhood without being labeled communist."

Weems recalled that Lasley arranged for UPWA air transportation --- a plane at Chicago's Midway Airport --- to fly meat from Rath to needy families victimized by racial violence in the South. That included the families of four girls killed in a Sept. 15, 1963 Birmingham, Ala., church bombing. He also arranged to transport union members to rallies.

Lasley was a vice president with the international for more than 20 years, even after the UPWA merged with the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen in 1968. He became director of the merged union's civil rights department.

At a speech in Waterloo in 1971 at the union's tri-state conference, Lasley noted changes for the better in Waterloo. He noted the YWCA had integrated before he left for Chicago in the late 1940s, and that despite continued strife in the community in the late '60s and early '70s, "Waterloo has done the best job of integrating the schools of any city I have seen." He also noted he was elected to his union leadership position by a majority vote of black and white workers. He asked conferees to continue to work on problems affecting women and minorities.