Covering 9-11: Day of sorrow, years or sacrifice, embers of hope

Posted

by Pat Kinney

on Friday, September 10, 2021

Pat Kinney of the Grout Museum District staff was a Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier reporter and editor from 1984-2018. He wrote this reflective piece for the Courier in 2021, 20 years after the 9-11 attacks.

So much has happened since Sept. 11, 2001. While it's increasingly distant, like a passing destructive storm, you never quite put it away in your mind. Because it, and the carnage left in its wake, has never completely gone away. And that makes you appreciate everything and everyone you hold dear in life.

Sept. 11, 2001 began for me with a telephone call shortly after 5 a.m.

My boss, Courier Editor Nancy Raffensperger Newhoff, was sick. She asked me to work for her.

I believe it was the first and only time Nancy called in sick in the 27 years she ran the Courier's news operation. So the day was unusual right off the bat.

But I'll never forget what she said to me.

"I don't think there's anything going on."

Three hours later, all hell broke loose.

A plane slammed into the World Trade Center in New York. I alerted the copy desk and copy editor Doug Hines, who was putting together Page 1 that day.

Then a second plane hit. My first conclusion was that it was a small plane and that the pilot had been rubbernecking watching the first crash, only to also crash --- something you hear about all the time on the highway.

It was more than that. It was another airliner. I believe it was Doug who said it was more than an accident.

Then we heard the Pentagon had been hit. It was much more than an accident. It was an attack.

"There was a palpable sense of people being stunned, but there was work to do and not much time. I think we all felt an enormous responsibility to do justice to a story of such gravity," Hines said in his recolletions of the day in 2006.

My longtime friend and mentor H. James Potter, at that time the Courier's regional editor, and myself looked at each other in disbelief.

We may have been thinking the same thing, but Jim got the words out first.

"Well, what are we going to do for a story?" Jim said.

What happened next was almost instinctive. I recalled some years earlier, when a TWA flight exploded and crashed off Long Island, we had used a directory of Waterloo public school graduates to locate former residents living in New York.

I grabbed that directory, plunked it down between a couple of reporters ---- former Courier staff writer Paul Sisson being one ---- and said, "Call every damn name on that list in New York City until you find somebody."

One of our own former staff writers, Jennifer Nardini, had just moved to New York. We contacted her as well. Other staffers recalled we had contacted Terry Wahl, a U.S. Customs Service employee working in the World Trade Center, during a previous bombing in 1993, and we made contact with Wahl's family as well..

Like every good staff on any paper worth its salt, everyone pitched in. Our work began to bear fruit, and I was amazed at what we had come up with.

We contacted several former Cedar Valley residents in New York, among them Patricia Sloan, a 1961 West High School graduate and retired investment banker who was walking four blocks north of the World Trade Center when she heard an explosion from the first plane.

"I looked up and one building was on fire," Sloan said, her voice shaking just 15 minutes after returning to her uptown Manhattan apartment.

It was absolutely incredible that we, halfway across the country from New York, had obtained practically an eyewitness account that close to the disaster. Sisson and staff writers Rebecca Kline and Jeff Reinitz did the main local story, but others were manning the phones as well.

Flights were grounded everywhere, including at the Waterloo Regional Airport, and staff writer Tim Jamison volunteered to go to the airport to check on the situation there and cranked out a story on deadline.

As is the case in any kind of crisis situation, minutes seemed like hours. And we had less than an hour to deadline for that afternoon's paper.

Doug and the other copy editors, who place the stories on the pages for each day's edition, quickly and professionally got the more routine news and pages out of the way to focus on this major story, and what would be a Page 1 for the ages --- though I doubt anyone was thinking of that, as much as just getting the job done right and on time.

"I don't remember anybody crying, but many seemed like they were on the verge of tears," Hines said. "The other thing about that morning was how the blows kept coming. The second tower hit. The Pentagon. Shanksville. I couldn't see a TV, but each bit of bad news brought a groan or worse from those who could. The worst moment after the first moment was when Saul (Shapiro, Courier editor) came out of his office to say one of towers had collapsed. The possibility had never occurred to me."

We were less successful making contacts at the Pentagon, but one response, which I could not use for publication that day, underscored the gravity and of the situation in terms of loss of life.

I e-mailed U.S. Navy Capt. Gerry Roncolato, the first commanding officer of the Navy destroyer USS The Sullivans, whom I'd met in 1997 --- ironically, in New York, during the ship's commissioning. On Sept. 11, 2001, he was working in the Pentagon. He could say nothing in an official capacity. But he indicated to me he had a lot of friends who wouldn't be going home to their families that evening.

"The rest of the day played out in a miasma of chaos, uncertainty and horror," Hines said. "Not knowing how many jets had been hijacked. Fighters scrambling. Air travel halted. The president and Congress in hiding. Initial reports as many as 50,000 could be buried in the rubble."

As one of the trade towers collapsed, then the other, personal feelings had to be pushed aside, but one remained in the back of my mind. I had recalled that the brother of one of my very best friends worked in lower Manhattan. His family had not heard from him since early that morning. He was in one of the buildings near the trade center that was evacuated.

I added him to the list of possible local contacts in Manhattan and asked one of our staff to try to reach him. We had heard nothing by deadline. Staff writer Charlotte Eby finally got through to him --- he had walked home to his residence on Manhattan's upper west side. He said to tell me hi. I almost lost it right there. I e-mailed his brother the news. He also had heard, and replied, "God Bless America." I had a lump in my throat as I read the words.

Nancy, not one to sit at home while a story this big was unfolding, called in about 9:30 a.m.

"What's going on? " she said, apparently having just turned on the television.

I assured her we had the situation in hand.

She called back less than 30 minutes later.

"I'm coming in," she said, sick and all. Some of us, knowing Nancy as we do, laughed. It was the morning's only light moment.

After Nancy arrived she called a quick staff meeting to plan the next day's paper, which would have to be a follow up with reactions to the disaster. Those two print editions, on Sept. 11-12, 2001 -- now seem an incredible feat in the days before online news and day-in-advance print deadlines.

The rest of the day, even the week, seemed like a blur.

Other previously scheduled assignments on my schedule, like the opening of the Best Buy store near Crossroads Center, seemed incredibly trivial.

A World War II veteran I'd worked with previously called and railed against the "God-damned Arabs" I let him vent to get him off the phone, though I was offended. My late uncle, also a World War II veteran, was an Arab American.

One of my assignments for the Sept. 12 paper was to visit Rabbi Sol Serber of Sons of Jacob Synagogue. As I pulled up in the synagogue parking lot off Vermont Street, I noticed a group of kids playing over at St. Edward School.

Though I was almost certain we were at war, as I watched those kids, on that beautiful sunny late summer day, I took a deep breath and had some hope that life would go on.

And it did. Twenty years of life’s milestones, and all the laughter and tears and everything that goes with them, have passed by.

But not for everyone.

The people who lost their lives that day, and the people who have sacrificed life, limb and physical and emotional well being for us since then, must never be forgotten.

I think of one of my daughter’s classmates whose leg was shredded by an IED while serving with the Marines in Iraq. I think of my friends in Iowa Army National Guard who have served multiple deployments. I think of the soldiers who lost their lives – some in combat, some later to suicide -- and their families and comrades I have come to know, who all still feel their loss. I think of the guys who came back maimed to still courageously live their lives surrounded by the love and support of family and friends.

I think of my dear friend who was waiting for word of his missing brother in Manhattan on 9-11. He and his wife sent their two sons serve in the military - one in the Army Rangers in Iraq, one in the Navy on undisclosed duty assignments. My friend was recently ordained a deacon in the Catholic Church and, thankfully, both his boys, now discharged, were there.

So comparatively few individuals and families have willingly bore the burden and stood the watch for the rest of us. Some are in my own family. I am so very proud of them, as would be my late dad and older brothers who served in World War II and during Vietnam.

I regret that my children, and so many other young people around the world, have grown up in a period of constant war. But I hope and pray that they are blessed with the wisdom and means to a better way.

I saw a glimpse of that in the days after Sept. 11, 2001 when I took my children out to dinner.

My son, then 7, asked me if kids ever died in a war. I had to tell him yes. I could see the growing sadness in his face.

My daughter, then 9, tried to console him by pointing to the bracelets we were wearing. A friend's children had made them to raise money for the Red Cross. The bracelets were made of many red, white and blue beads, with four black beads for each of the airliners lost. My daughter saw a different symbolism.

"See those?" my daughter told her brother, pointing to the black beads. "That's how many bad people there are in the world.

"See those?" she said, pointing to the more numerous red, white and blue beads. "That's how many good people there are in the world."

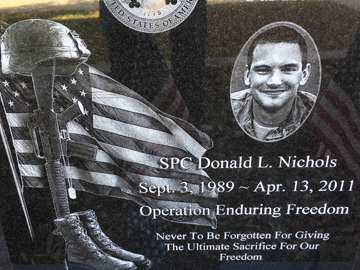

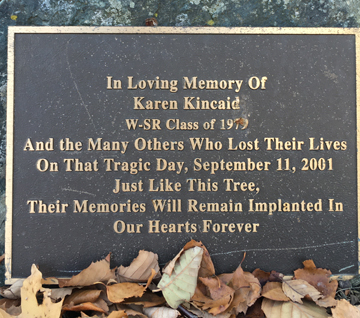

Memorial markers at Waverly-Shell Rock High School for alums Donny Nichols, killed in Afghanistan in 2011 serving with the Iowa Army National Guard, and Karen Kincaid-Batacan who was on American Airlines Flight 77 which hit the Pentagon on 9-11.